Join us on a voyage into the secret heart of apatite and discover the spellbinding beauty of this little-known gemstone.

Apatite is very much an insider gemstone collectors’ secret largely unknown to the general public. Occurring in a kaleidoscope of colours – including an electrifying shade of neon blue often confused with the Paraiba tourmaline –apatite is considered a prized possession among collectors. Join us on a voyage into the secret heart of apatite and discover some of the jewellers who have been bewitched by this magical stone just waiting to be unearthed.

What is apatite?

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals found in abundance in nature, in the human body in the form of tooth enamel and bone mineral, and even in Moon rocks brought back to Earth by Apollo astronauts. As the world’s most common source of phosphorous, some forms of apatite are used in the manufacture of fertilizers, acids and chemical products.

Transparent gemstone-quality apatite, however, is extremely rare and, due to its softness, not often used in jewellery. Apatite scores 5 on the Moh’s Scale of Hardness – designed to measure the resistance of minerals to being scratched, with 10 represented by a diamond and 1 by talc – and recognition of the gemstone still flies under the radar.

It is hard to cut because of its brittle nature and is prone to lose its lustre on contact, very few mainstream jewellers experiment with apatite in their creations, and most of it ends up in the hands of collectors in either raw, faceted or cabochon-cut stones,because it can be easily scratched.

How apatite got its name

German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner christened the stone apatite, derived from the Greek word apatein, meaning “to deceive or be misleading” because of the stone’s chameleonic ability to look very much like other stones. In fact, it is often mistaken for peridot, topaz, aquamarine, tourmaline and beryl, depending on its colour.

Colours, cat’s eye cabochons and countries

A particularly rare and mesmerising form of the stone displaying chatoyancy, or cat’s eye effect, occurs in crystals of apatite with fibrous, needle-like inclusions. Gemstone-quality apatite occurs in a rainbow of enticing colours: neon blues and greens, petrol blues, deep purples or violets and golden yellows. To appreciate the beauty of this unusual optical phenomenon, the stones are cabochon-cut. Particularly appreciated for their chatoyancy are intense blue apatite stones from Burma and Sri Lanka and green, blue and yellow varieties from Brazil.

Where is apatite found?

Deposits of apatite have been found in Brazil, Madagascar, Burma, East Africa, Mexico, Canada, Russia and Sweden, and there is even a Spanish variety called the asparagus stone because of its yellowish-green colour. I contacted Spanish gemmologist Adolfo de Basilio while he was buying and selling stones at Munich’s Mineralworld Show to find out his thoughts on this enigmatic gemstone. “My absolute favourite apatites are the Madagascar blues – those ones with a swimming pool-blue that can rival the Paraiba tourmaline,” he says. “Other beautiful apatite stones can be found in San Luis Potosí, Mexico.”

Canadian-born designer Kat Florence has an eye for rare gems and hunts down unusual stones from all over the world. She “discovered” neon apatite two years ago while travelling through Bahia in Brazil. “Its colour rivalled the finest quality and most valuable Paraiba tourmalines at a fraction of the price,” she says.

The value of apatite depends primarily on colour saturation, so specimens with a high colour intensity command the best prices. Size does matter when it comes to apatite since finding large stones weighing over one carat is extremely rare.

Working with apatite in jewellery

Maria Frantzi, a Greek jewellery designer based in Rotherhithe, London, fell in love with the exquisite colour range of apatite and the affordability of the stone yet was aware of the innate difficulties of working with a very soft stone, which is unsuitable for rings or any other kind of jewellery exposed to a lot of contact. As Frantzi explains: “Both my parents were jewellers and I grew up in a jewellery-intense environment and learned to appreciate craftsmanship. My jewellery has to be married to good technique; it has to be proper jewellery and robust enough to stand the test of time.” Working with the inherent limitations imposed by apatite put all her creative juices to the test until one day “I had an epiphany,” she says.

To allow her to use apatite to its full potential, Frantzi came up with a two-decker or three-decker sandwich system. To protect the surface of an apatite stone on a ring, for example, Frantzi employs a doublet in which a slice of rock crystal is placed on top of the apatite. The doublet of rock crystal can be faceted or left in the rough, creating some spectacular effects and providing a roof over the apatite’s delicate head. A triplet involves an additional sliver of mother-of-pearl placed underneath the apatite, allowing the stone to radiate a delicate iridescence. Frantzi’s favourite colour is petrol blue, and using apatite stones means she can keep her prices at a reasonable level.

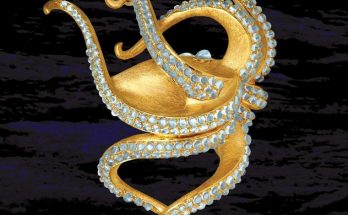

Kat Florence prefers the neon-blue variety of apatite from Bahia, Brazil, and Caribbean blues from Fort Dauphin, Madagascar, which she sets alight with diamonds. “The disadvantage of working or wearing apatite is that you must be knowledgeable about the softness of the gemstone and how to care for it,” she says. Her customers are more interested in apatite rings than pendants or necklaces because, adds Florence, “a ring allows you to view its beauty while you wear it”.

Another designer who has recently started working with apatite is Greece’s Nikos Koulis. His Yesterday collection, with its pervading Art Deco spirit, embraces apatite in rings, earrings and pendants blending dazzling turquoise with diamonds and black enamel.